Guns, Dogs and the American Fear of Accountability

After hearing today’s news of a two-year-old mauled to death by two Rottweilers, I couldn’t stop thinking about the parallels between how America treats guns and how it treats dogs. Both are powerful tools that demand knowledge, discipline, and structure. Yet in the United States, both are handed over freely, with no questions asked, no qualifications required, and no meaningful accountability imposed.

This is a country where you need a license to drive a car, to cut someone’s hair, to serve alcohol at a bar, but not to own a firearm capable of mass killing. And not to own a dog capable of killing a child.

Anyone can walk into a shelter or pet store and adopt or purchase a high-drive working breed, often bred for guarding or combat, with zero knowledge of canine behavior, zero understanding of risk, and no legal requirement to learn. It’s the same reckless access Americans have to deadly weapons, paired with the same refusal to reckon with the consequences.

A few months ago, I wrote a paper titled What if “Adopt, Don’t Shop” is Doing More Harm Than Good? It was a critical examination of dog ownership, public policy, and ethical breeding. I argued that America built a culture of social irresponsibility that fails to protect both people and animals.

Every year, thousands of serious injuries and fatalities are caused by dogs. Most of them are preventable. But instead of addressing the structural causes, poor education, lack of regulation, and absence of owner accountability, the conversation collapses into internet outrage and superficial blame.

And it’s not just about dogs. As a European who moved to the U.S., I see the same pathology at work across American society: a kind of national allergy to responsibility. Because if Americans can’t agree that semi-automatic weapons should require training and licensing, what hope is there for asking them to take a basic safety course before owning a 100-pound predator?

Americans love to say, “It’s not the gun, it’s the person.”

Well, it’s not the dog either.

It’s the person, the human who failed to learn, to lead, to train, to prepare. The one who took power over another life without earning it.

In the United States, freedom has been mythologized as doing whatever you want, not as earning the right to do something well. It’s a country born from rebellion, built on rugged individualism, and addicted to the idea that control equals oppression.

Where This All Comes From: A Cultural Diagnosis

The Six reasons for America's Resistance to Responsibility

To understand why the idea of licensing gun or dog ownership is so often dismissed as “un-American,” we must examine the country’s founding narratives and inherited assumptions. The roots of this cultural dysfunction are not just political. They are psychological, historical, and mythological.

Here are six key foundations that help explain why regulation, even when it saves lives, is treated in America not as civic prudence, but as sacrilege.

1. The Frontier Myth and the Cult of Self-Reliance

Source: Founding Fathers & Gun Rights – U.S. Constitution.net

America was born on a frontier. Early settlers were not building upon centuries of social institutions.

They were violently carving out survival on stolen Indigenous lands. In this environment, the gun was more than a tool; it was identity, a symbol of autonomy, masculinity, and moral independence.

This mythology of the lone, self-reliant frontiersman has endured long after the frontier closed.

It became embedded in American consciousness as proof that the strong don’t need rules. The idea that survival requires structure or collective responsibility is, for many Americans, not just foreign, it’s offensive.

The dog, like the gun, becomes a tool of this narrative: a property. Not a life with needs and instincts, but an extension of one’s control.

2. Anti-Tyranny as Founding Narrative

The American Revolution was a rebellion not just against taxation, but against the very idea of centralized power.

The Second Amendment, often treated as inviolable doctrine, was born from a very real fear of centralized authority. In its original context, it was a check against standing armies and government overreach. But over the centuries, this historical safeguard morphed into a broader ideological stance: that citizens must remain armed to keep the state in check. No other democracy mythologized this idea to the same extent.

In Europe, where states developed earlier, legitimacy came from institutions; in the U.S., it came from resistance to authority.

This narrative, however anachronistic, continues to dominate American discourse around personal rights. In such a framework, any attempt at regulation is immediately suspect.

To require training before owning a gun, or to mandate behavioral understanding before adopting a potentially dangerous dog, becomes conflated with state oppression. Rights are assumed to be self-evident and unconditional, even when the consequences of exercising them poorly fall on others.

In this light, asking someone to pass a basic dog ownership course isn’t seen as common sense. It’s seen as government overreach.

3. The Racial Subtext: Control, Surveillance, and Social Hierarchies

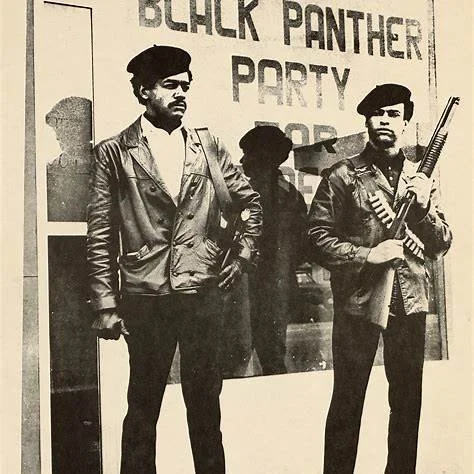

Black Panther Party national chairman Bobby Seale (left) and defense minister Huey P. Newton standing in front of the Black Panther Party's headquarters, Oakland, California, c. 1971

There’s a darker layer: guns have always been tied to social and racial hierarchy. From early slave patrols to Reconstruction-era militias to the modern NRA’s political transformation following the civil rights movement, firearms have been used as tools of social control, particularly in service of maintaining white dominance.

The sight of armed black men asserting their constitutional rights was, and remains, a trigger for panic in white political consciousness.

After the Civil War, armed white militias (like slave patrols and later the KKK) enforced racial order and suppressed Black emancipation.

Even the NRA, originally a marksmanship club, only became a political powerhouse after the civil rights era, when the image of the “armed Black man,” embodied by the Black Panthers, was weaponized to galvanize the modern conservative gun rights movement

Similarly, breed-specific dog ownership has long intersected with questions of class, race, and perceived threat.

These breeds are often racially and economically coded, associated in the public imagination with marginalized communities, particularly working-class Black and Latino neighborhoods. They are seen, sometimes unfairly and often sensationalized, as extensions of their owner’s threat profile. In this way, the dog becomes not only a companion or protector but a symbol of power in a society that routinely disempowers its owner.

To own a powerful breed in America is, for many, an act of defiance, a reclamation of control in a system that offers little structural protection. For those with fewer institutional resources (policing, housing security, legal recourse), a strong dog becomes both a shield and a statement. It is personal safety, emotional security, and social armor all in one. But this also makes the issue of regulation profoundly charged.

Attempts to regulate breed-specific ownership (through bans, licenses, or restrictions) are quickly interpreted not just as public safety measures, but as cultural policing. For many, particularly those in disenfranchised communities, it feels like an extension of the same surveillance and control they already experience in other forms: redlining, over-policing, eviction, incarceration. The conversation becomes less about canine behavior and more about who gets to be trusted, who is seen as “responsible,” and who is allowed to own power without oversight.

This reflexive opposition to regulation is not always rooted in rational policy analysis, but in historical trauma: the trauma of always being the one regulated, the one presumed dangerous, the one not granted the benefit of the doubt. In that context, the refusal to accept limits on dog ownership, like the refusal to accept limits on gun ownership, is not purely about liberty. It’s about resisting further marginalization, about defending an identity already under siege.

Thus, any conversation about breed-specific legislation, dog ownership standards, or public safety must contend with these deeper layers. Without addressing the historical inequities that shape who owns what and why we risk treating symptoms instead of causes.

We must understand that regulation without equity becomes oppression, but freedom without responsibility becomes violence.

4. Neoliberal Individualism and the Erosion of Public Trust

Since the Reagan era, American political culture has increasingly emphasized personal responsibility over collective welfare. Government has been framed as inefficient, bureaucratic, or even predatory, while the private citizen is imagined as a hyper-competent self-steward. This neoliberal ethos champions autonomy but erodes trust in institutions, especially those designed to protect the public good.

In this context, the idea that you should need certification to own a gun or a dog feels, to many Americans, like government intrusion into private life. But what it actually reflects is a broader distrust: that no system, no professional, no agency has the right to determine who is fit for power or protection.

The irony, of course, is that the same culture that demands individual liberty often fails to take individual responsibility, especially when others are harmed by that freedom.

5. Masculinity in Crisis: Power, Performance, and Projection

From an article on Politico

Cultural sociologists have long observed that American masculinity is increasingly performative, defined not by character or competence, but by visual markers of dominance.

This anxious attachment to firearms isn’t just about safety, it’s often about identity. Guns fill a void left by shifting gender roles, economic decline, and the breakdown of traditional social structures.

Men are seeking external symbols of control.

If you’re interested in exploring how this ties into broader questions of masculinity and cultural anxiety, I highly recommend the Politico article: “The Crisis Over American Manhood Is Really Code for Something Else.”

The gun and the aggressive dog have become two such symbols. They are not simply tools. They are projections of defiance, identity, and unresolved fear. The open-carry demonstrator, the backyard breeder advertising “protection dogs”: these are not just individuals. They are participants in a larger cultural performance, one rooted in the desire to appear unchallengeable in a world that increasingly feels uncertain.

These are expressions of anxiety, performed as defiance.

6. The Absence of a Collective Memory of War

Another reasons for America’s continued glorification of violence, whether through guns, dogs, or media, is its geographical and emotional distance from the catastrophic violence of the 20th century's great wars.

Unlike Europe, the United States never experienced the physical devastation of modern warfare on its own soil.

America never had to reconcile with the trauma of mass graves. Its cities were not flattened by bombs. Its civilian population was not occupied. Its people did not return home to ruins and scarred landscapes where tens of millions had perished.

This spatial and psychological distance has allowed Americans to romanticize violence as well as weaponry, and to frame it as virtuous, redemptive, and even heroic, and ultimately to keep its myths and national archetypes intact: The cowboy, the soldier, the lone defender, the police dog, the armed homeowner.

It emerged victorious, untouched, and economically booming, ushering in the golden age of suburban expansion.

With that came the reinforcement of an old narrative: that violence, when wielded by the “right” side, is not only justified, but noble.

In contrast, in Europe as well as in Japan we emerged from the trauma of two world wars, with a collective commitment to regulation, demilitarization, and institutional restraint. We created systems designed to prevent future violence by building strong gun control laws, robust social safety nets, and a shared ethic that security is a collective responsibility, not an individual right to exert force.

Sadly here in America, the answer to violence is more dominance, not more cooperation. More weapons, not more wisdom. More ownership, not more oversight.

Freedom, Misunderstood: Power Without Responsibility

In all of these threads, a consistent pattern emerges: the American conception of freedom is deeply entangled with resistance to earned responsibility, and power is treated as a right to be exercised, not a privilege to be earned. Guns and dogs both represent a kind of power.

This refusal has consequences. Deadly ones.

Every year, children die. Postal workers are mauled. Family pets are torn apart. Dogs are euthanized. And the conversation remains stuck on symptoms: bad breeds, bad apples, bad luck, rather than root causes.

As with guns, the core problem isn’t the object. It’s the unqualified person wielding it.

Until American culture is willing to reimagine freedom as a shared responsibility and as something earned through education and stewardship, rather than granted by default and exercised without guardrails, tragedies like the one that sparked this reflection will continue.

The funerals will continue. The excuses will repeat. Because in America, freedom has become the ultimate alibi, even when it kills a child.

They are not accidents. They are the predictable result of a cultural design.